Crossing Over

Chapter 8

Coming Too Late for Raymond

They visit in the living room, Mary Lee on the couch under a portrait of King, Raymond across the room in a straight-backed chair. For long stretches, they say nothing, Raymond staring at his big sister, Mary Lee staring at her feet.

He lives by himself in this tiny brick house--the floor canting like the deck of a ship, the sink full of dirty dishes--counting the minutes until Mary Lee comes.

It's Raymond but it's not Raymond, she says, because he hasn't been right since the accident 20 years ago. She's not sure what happened, and Raymond can't say. She only knows that, while driving around Gee's Bend, he skidded off the road and flew from the car, then writhed in a ditch until someone saw him and ran to get Mary Lee.

Everything be all right, Mary Lee told him, sobbing, peering down the road for the ambulance, everything be all right.

With no ferry, the ambulance had to come around the river, as it must each time a Bender has a seizure, a heart attack, an accident. The paramedics took two hours to reach Raymond that day, and while waiting, he suffered a stroke.

If a ferry comes, Mary Lee says, it will be too late for Raymond. Too late by 20 years.

Outsiders often ask why Benders like Mary Lee don't just leave, and one reason has always been true: Most have Raymonds. While Mary Lee was in the hospital, her sister checked on Raymond, cooked his meals and washed his clothes. But what would happen to Raymond if Mary Lee left, or died?

What would happen to him if a ferry came, carrying people less patient, less kind than his fellow Benders. She studies Raymond, his eager expression the opposite of her faraway look. Always right here, right now, he's always more vulnerable to strangers than she.

While Mary Lee studies him, Raymond studies the portrait of King.

'I have a dream,' Mary Lee says, reading his mind.

Raymond smiles.

'He had one, too,' Mary Lee assures him.

As a boy, Raymond was a history buff. 'He'd write everything down,' Mary Lee says. 'All the history of Gee's Bend. Since the accident, he can't catch up with everything like he used to.'

“Gee's Bend history has more remote bends than the river.”

She tries to catch up for him. The trouble is, Gee's Bend history has more remote bends than the river. Almost nothing is known, for instance, about the decades after the Civil War, when Benders kept the river wrapped around themselves like one of their quilts, remaining so isolated from the outer world that other Alabama blacks called them 'The Africans.' When Pa-Petty was born in 1866, Benders still spoke a hodgepodge of backwoods English and African dialect, and held fast to ancient superstitions. If you sit on a log, you'll soon be disappointed. If you travel at night with whiskey in your pocket, the dead will follow on your heels.

This much Mary Lee knows: Half her neighbors and cousins and girlfriends are named Pettway because a white man named Mark Pettway left his North Carolina plantation in 1847 and came here with 100 slaves in tow. He formed a caravan of covered wagons, to keep his family and furniture dry, and marched his human possessions alongside, a 700-mile trek through December rain and cold. Only one slave was allowed to ride--the cook. Pettway wanted her fresh to prepare the meals.

Before Pettway, Gee's Bend was owned by a shadowy 57-year-old bachelor named Joseph Gee, the first white man to stake his claim here. In 1820, Gee and his slaves tamed the swamp and cleared the land, which would forever bear his name and their progeny. When Pettway arrived, he threw his slaves among Gee's slaves and named them all Pettway. Today, nearly every Bender is connected to the merger of those two slave clans. Though Mary Lee's last name is Bendolph, her grandmother was a Pettway, her daughter married a Pettway, Pa-Petty married a Pettway, and so on.

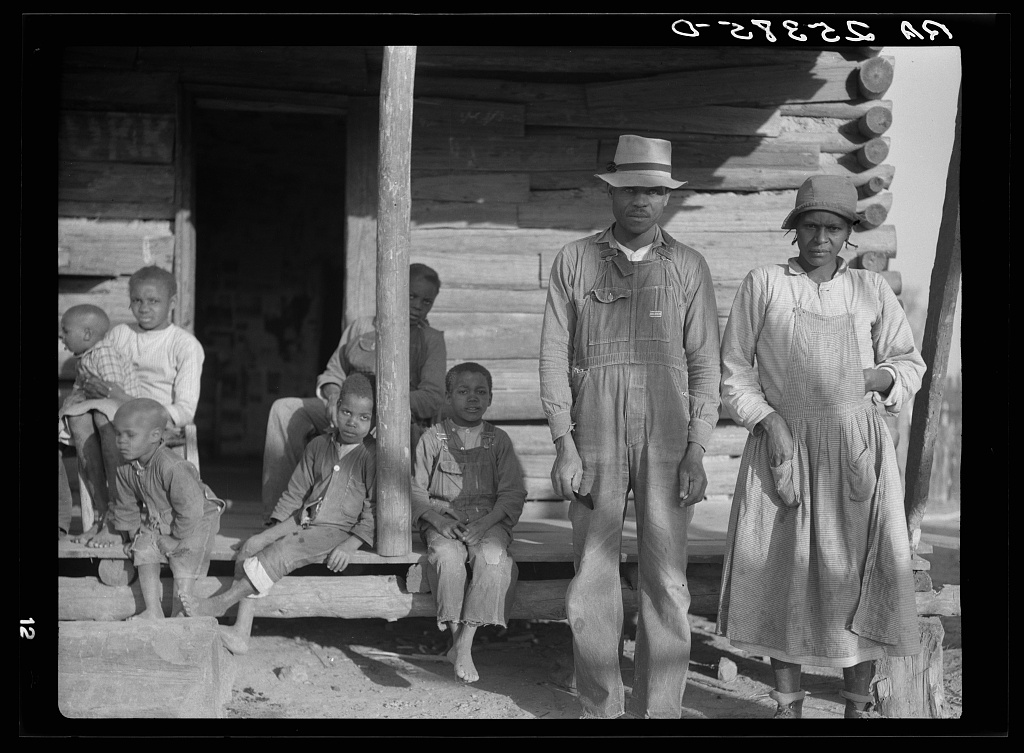

Pettway family group. Arthur Rothstein, 1937. Sourced from Library of Congress.

In Pettway's day, Mary Lee's river was crowded with ships. They passed Gee's Bend day and night, ferrying planters and miners, gamblers and dandies, stevedores and cotton kings. Many emitted a ghostly calliope music, the music of merry-go-rounds and other things that go in circles.

One of the grandest of all, the Orline St. John, caught fire and sank off Gee's Bend in 1850. A slave named Abram swam out and saved nine men, who were carried with other survivors to the Big House, a makeshift hospital that day. Scores drowned, however. At least one was laid to rest in Camden.

Surely Master Pettway attended the funerals. And if he did, he went the long way, taking the same road his caravan took into Gee's Bend, the same road Martin Luther King's caravan took, because it would be another 20 years before his son would build the first ferry ever at Gee's Bend.

History of Gee's Bend

Scroll side-to-side to navigate

Pettway knows. Better than anyone, he could tell Mary Lee the history she longs to hear. She passes him every day too, but unlike most of the dead, he keeps silent, as mute as Raymond and Aola. He just lies there, in a snake-infested copse of trees not far from Raymond's front door.