Crossing Over

Chapter 4

A Community of Survivors

Mary Lee rises with the river birds and changes her 87-year-old mother's diaper, then straightens the house, then feeds her three grandsons, then feeds her six cows, then drives her mother around the river for one of the frequent checkups Aola Bendolph requires now that Alzheimer's has left her frail and mute.

They start up County Road 29, the only road in and out of Gee's Bend. A two-lane blacktop, it forms a perfect circle at the bottom of the U, then winds north, past dense woods and slow-moving creeks, through shade-drenched meadows and one unexpectedly beautiful valley.

At the top of the U, they turn left on Alabama Highway 5, headed south with the river, then cross a bridge below William 'Bill' Dannelly Reservoir, named after the judge who denied a request from Benders, heartsick after King's assassination, to re-christen their community King, Ala. Instead, Gee's Bend was renamed Boykin, after a senator Benders had never heard of. Regardless, Benders still say Gee's Bend, as do road signs. Mary Lee pronounces it in a prayerful mumble that sounds like 'Jesus been.'

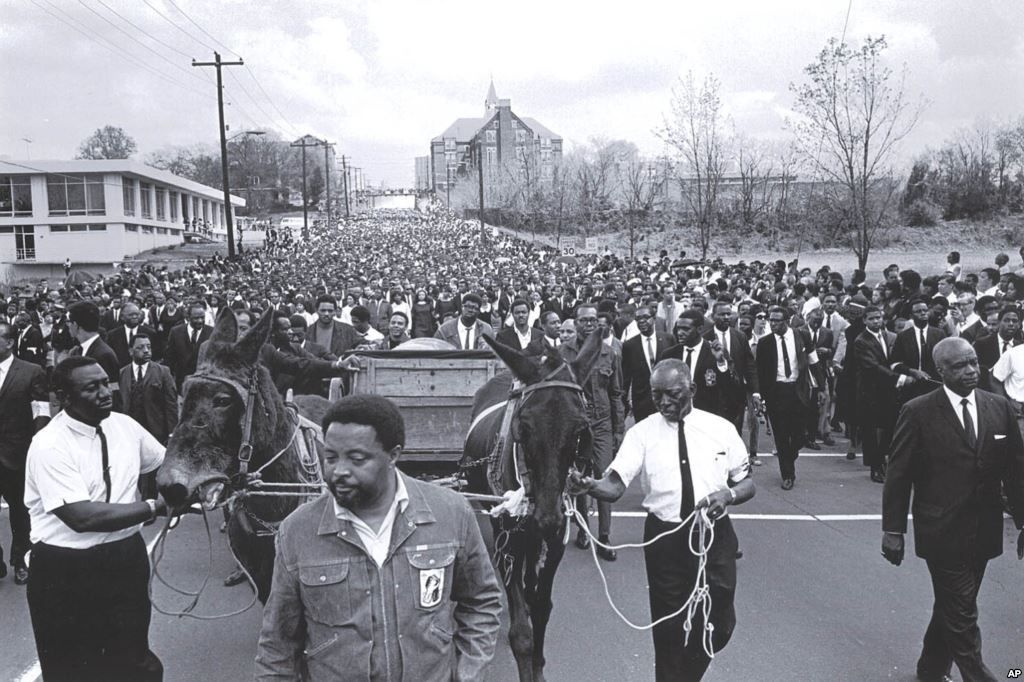

Name or no name, Benders were able to honor King in their own way. The two farm mules that pulled King's casket through the streets of Atlanta came from Gee's Bend.

Two farm mules from Gee's Bend pull King's casket through the streets of Atlanta.

Across the river now, Mary Lee and her mother come to the Camden town square--jail, bank, courthouse, Curl's newspaper. From Mary Lee's front door, it's a distance of only four miles as the red-tailed hawks fly, but it's an hour's drive around the river, which is why Mary Lee's Chevy Corsica has grown old before its time.

The trip leaves both women spent. In the doctor's examination room, Aola slumps forward in her wheelchair, muttering, laughing at nothing. Mary Lee leans against the wall, glasses slipping down her nose, a faraway look fixed tight on her face. She's thinking about scheduling a doctor's visit for herself, to find out why she's been 'heaving,' why she's been urinating blood.

The room is cold and bare, except for the walls, hung with black-and-white photographs of Gee's Bend in bygone days. Baptism in the river. Girl in a cotton patch. Ferry crossing to Camden. Mary Lee eyes each one.

'We have people ask about those pictures all the time,' the nurse says. 'But they were taken so long ago, no one knows anything about them.'

'I know,' Mary Lee protests. 'These my people.'

'What?' the nurse asks.

'This Roman,' Mary Lee says. 'That Rissa, that Cassie, this Perkin . . . .'

The nurse watches, mouth agape, as Mary Lee goes around the room, identifying the long dead.

White folks have always felt compelled to record Gee's Bend. Writers, students, storytellers, anthropologists, photographers, reporters, all sorts of strangers have come shambling down the one road in and out of Gee's Bend, especially since the road got paved in 1967, fulfilling a promise King made the night he came.

These photographs in the examination room are blurry and unremarkable, but others of Gee's Bend hang in museums, including one of Artelia Bendolph, first cousin to Mary Lee's husband. She was 10 years old when Arthur Rothstein made his way to her loblolly pine cabin, beneath a massive chinaberry tree. At the depths of the Great Depression, the federal government hired Rothstein to find and photograph the poorest of America's poor. He found them in Gee's Bend. In Artelia, he met their queen.

Among the many images Rothstein made--the ghostly Big House, its elegant cornices and fanlights still intact; the sad slave cabins, dung and newspaper stuffed in their cracks; the womenfolk teaching girls to piece artful quilts with rags, 'the onliest way we had to keep warm,' says neighbor Lucy--none achieved the power of Artelia. Hair in cornrows, face in gentle repose, she stood at the glassless window of her cabin, a faraway look on her face.

Girl at Gee's Bend. Arthur Rothstein, 1937. Sourced from Library of Congress.

Artelia never got far from that cabin, but her face went around the world. Novelist William Saroyan wrote a poem to her beauty: 'Behold ... a young queen, not on a barge on the Nile a thousand years ago, but right where she is and right now.' Something about that face, that look, spoke to Saroyan of rivers, and royalty.

Today, Mary Lee lives on the very spot where Artelia was photographed. The cabin's gone, and Mary Lee chopped down the chinaberry herself. In their place stands Mary Lee's green-shuttered house, second of the Bend's 'Roosevelt houses,' so called because President Franklin D. Roosevelt rebuilt Gee's Bend and saved its people from starvation.

In the early '30s, Roosevelt learned that hundreds of slave descendants were dying on a U-shaped peninsula in Alabama. After the stock market crashed, cotton had swooned to a nickel per pound, and Benders couldn't grow enough to pay for seeds and supplies. A Camden merchant had been advancing them what they needed, warehousing their cotton until prices rose again. But when the merchant died, he left no records--and one ruthless widow.

It was a cool day in autumn. Armed with pistols, the widow's henchmen came by the ferry and went from cabin to cabin, closing out debts, settling accounts, robbing Benders blind. They took everything--tools, wagons, plows, furniture, eggs, hogs, mules--then wended like a funeral procession back to the river.

Mary Lee's father, Wisdom, sat in the dirt and wept. He might have given up, might have gone under, but for Mary Lee's mother. "She told him, 'Don't cry,' ' Mary Lee says. 'She told him, 'Everything be all right, everything be all right.'"

They survived that winter on wild plums and blackberries. They killed squirrels with slingshots and fished some. The Red Cross sent meal and meat, but life didn't get better until Roosevelt came to the rescue. He granted 100 families in Gee's Bend low-interest loans to buy modest farms and build new houses, with real glass windows and hardwood floors, the first some Benders ever set foot on.

New and old home of Clay Pettway. Arthur Rothstein, 1937. Sourced from Library of Congress.

Today, aside from a smattering of trailers, every Bender lives in a Roosevelt house, and much of Gee's Bend looks as it did in Roosevelt's day. Cows still have the right of way. Buzzards still circle overhead. And 100 homesteads still sit along red dirt lanes, in slightly uneven rows, like Monopoly houses.

Mary Lee's memories of those days--wearing a fertilizer sack for a dress, picking cotton alongside her mother, sleeping 12 to a bed on a mattress stuffed with cornhusks--remain clearer than any Rothstein photograph. So clear, she can hardly believe Wisdom's in the ground 22 years now and Aola sits in her own permanent posture of defeat.

'Ready for your shot?' the nurse asks Aola.

'She don't talk,' Mary Lee says. 'Sickness took everything but the laughter.'

The nurse swabs Aola's arm with cotton. Then, the needle. Aola jerks forward, laughing. Mary Lee puts a hand on her shoulder.

'Everything be all right,' Mary Lee says. 'Everything be all right.'